34 M11U: Samples and Populations

This chapter draws on material from Introductory Statistics by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Changes to the source material include light editing, adding new material, deleting original material, rearranging material, and adding first-person language from current author.

The resulting content is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

34.1 Introduction

In statistics, we generally want to study a population. You can think of a population as a collection of persons, things, or objects under study. To study the population, we select a sample. The idea of sampling is to select a portion (or subset) of the larger population and study that portion (the sample) to gain information about the population. Data are the result of sampling from a population.

Because it takes a lot of time and money to examine an entire population, sampling is a very practical technique. In U.S. presidential elections, for example, there are millions of potential voters, and it would be highly impractical to survey all of them. Instead, opinion poll samples of 1,000–2,000 people are taken. The opinion poll is supposed to represent the views of the people in the entire country. Likewise, manufacturers of canned carbonated drinks take samples to determine if a 16 ounce can contains 16 ounces of carbonated drink—this is a lot more effective than checking all of the cans!

From the sample data, we can calculate a statistic. We’ve been using the word statistics in a more general sense up until now, but it’s worth paying attention to a more specific definition: Formally speaking, a statistic is a number that represents a property of the sample. For example, if we consider one math class to be a sample of the population of all math classes, then the average number of points earned by students in that one math class at the end of the term is an example of a statistic. The statistic is an estimate of a population parameter. A parameter is a numerical characteristic of the whole population that can be estimated by a statistic. Since we considered all math classes to be the population, then the average number of points earned per student over all the math classes is an example of a parameter.

One of the main concerns in the field of statistics is how accurately a statistic estimates a parameter. The accuracy really depends on how well the sample represents the population. The sample must contain the characteristics of the population in order to be a representative sample. In inferential statistics, we are interested in both the sample statistic and the population parameter.

34.2 Samples

As mentioned earlier, gathering information about an entire population often costs too much—or is virtually impossible. Instead, we use a sample of the population. Ideally, a sample should have the same characteristics as the population it is representing.

Most researchers use various methods of random sampling in an attempt to achieve this goal. There are several different methods of random sampling. In each form of random sampling, each member of a population initially has an equal chance of being selected for the sample. Each method has pros and cons. The easiest method to describe is called a simple random sample. Any group of individuals is equally likely to be chosen as any other group of individuals if the simple random sampling technique is used. In other words, each sample of the same size has an equal chance of being selected.

When you analyze data, it is important to be aware of sampling errors and nonsampling errors. The actual process of sampling inherently causes sampling errors—this is the kind of error we try to minimize rather than entirely avoid. For example, if a sample is not large enough, we try to collect a larger sample—however, as we’ve already established, the whole point of sampling is because we don’t want to collect all of the available data, so there’s always going to be some kind of gap. Nonetheless, as a rule, the larger the sample, the smaller the sampling error. Factors not related to the sampling process cause nonsampling errors. A defective counting device can cause a nonsampling error. This kind of error is a bigger deal, and we need to get rid of it as much as possible

In statistics, a sampling bias is created when a sample is collected from a population and some members of the population are not as likely to be chosen as others (remember, each member of the population should have an equally likely chance of being chosen). When a sampling bias happens, there can be incorrect conclusions drawn about the population that is being studied.

34.2.1 Variation in Samples

Variation is present in any set of data. For example, 16-ounce cans of beverage may contain more or less than 16 ounces of liquid.

Measurements of the amount of beverage in a 16-ounce can may vary because different people make the measurements or because the exact amount, 16 ounces of liquid, was not put into the cans. Manufacturers regularly run tests to determine if the amount of beverage in a 16-ounce can falls within the desired range.

Be aware that as you take data, your data may vary somewhat from the data someone else is taking for the same purpose. This is completely natural. However, if two or more of you are taking the same data and get very different results, it is time for you and the others to reevaluate your data-taking methods and your accuracy.

To reiterate, two or more samples from the same population, taken randomly, and having close to the same characteristics of the population will likely be different from each other. Suppose Doreen and Jung both decide to study the average amount of time students at their college sleep each night. Doreen’s sample will be different from Jung’s sample, but neither would necessarily be wrong! Can you think of what would lead these samples to be different from each other?

34.2.2 Sample Sizes

If Doreen and Jung took larger samples (i.e. the number of data values is increased), their sample results (the average amount of time a student sleeps) might be closer to the actual population average. But still, their samples would be, in all likelihood, different from each other. Still, the size of a sample (that is, the number of observations) is important. Samples of only a few hundred observations, or even smaller, are sufficient for many purposes. In polling, samples that are from 1,200 to 1,500 observations are considered large enough and good enough if the survey is random and is well done. However, be aware that many large samples are biased. For example, call-in surveys are invariably biased, because people choose to respond or not.

34.3 Probability

It is often necessary to “guess” about the outcome of an event in order to make a decision. Politicians study polls to guess their likelihood of winning an election. Teachers choose a particular course of study based on what they think students can comprehend. Doctors choose the treatments needed for various diseases based on their assessment of likely results. You may have visited a casino where people play games chosen because of the belief that the likelihood of winning is good.

Probability is a measure that is associated with how certain we are of outcomes of a particular experiment or activity. An experiment is a planned operation carried out under controlled conditions. If the result is not predetermined, then the experiment is said to be a chance experiment. Flipping one fair coin twice is an example of an experiment.

A result of an experiment is called an outcome. The sample space of an experiment is the set of all possible outcomes. The uppercase letter is used to denote the sample space. For example, if you flip one fair coin, where = heads and = tails are the outcomes.

An event is any combination of outcomes. Upper case letters like and represent events. For example, if the experiment is to flip one fair coin, event might be getting at most one head. The probability of an event is written .

The probability of any outcome is the long-term relative frequency of that outcome. Probabilities are between zero and one, inclusive (that is, zero and one and all numbers between these values). means the event can never happen. means the event always happens. means the event is equally likely to occur or not to occur. For example, if you flip one fair coin repeatedly (from 20 to 2,000 to 20,000 times) the relative frequency of heads approaches 0.5 (the probability of heads).

To calculate the probability of an event , count the number of outcomes that lead to event and divide by the total number of outcomes in the sample space. For example, if you toss a fair dime and a fair nickel, the sample space is where = tails and = heads. The sample space has four outcomes; if we define as getting one head, there there are two outcomes that meet this condition: . So .

Roll2dice, by Niyumard, is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Let’s look at a slightly more complex example: rolling 2 six-sided dice. As seen in the image above, there are 36 different outcomes to rolling two dice. However, those outcomes are distributed in a way that some events are more likely than others. Let’s think about 11 events that are tied to getting a particular number, from two to twelve. As the image demonstrates, 6 out of those 36 outcomes add up to 7. However, only 5 out of 36 outcomes add up to either 5 or 8, and once we get out to 2 or 12, there’s only a 1 in 36 chance of getting what you want. So, there’s a much higher probability for the event of rolling a 7 than for the event of rolling a 12.

However, there’s an important detail in here. If you were to roll two six-sided dice 36 times, you would not be surprised if your observed results did not match the theoretical probabilities shown above. If you were to roll two dice a very large number of times, you would expect that approximately 6/36 (1/6) of the rolls would result in an outcome of 7. You would probably not expect exactly 6/36, though. The long-term relative frequency of obtaining this result would approach the theoretical probability of 6/36 as the number of repetitions grows larger and larger.

This important characteristic of probability experiments is known as the Law of Large Numbers which states that as the number of repetitions of an experiment is increased, the relative frequency obtained in the experiment tends to become closer and closer to the theoretical probability. Even though the outcomes do not happen according to any set pattern or order, overall, the long-term observed relative frequency will approach the theoretical probability.

34.4 Expected Values and the Law of Large Numbers

The expected value is often referred to as the “long-term” average or mean. This means that over the long term of doing an experiment over and over, you would expect this average.

You toss a coin and record the result. What is the probability that the result is heads? If you flip a coin two times, does probability tell you that these flips will result in one heads and one tail? Not necessarily! You could conceivably toss a fair coin ten times and record nine heads. As I suggested earlier, probability does not describe the short-term results of an experiment. Instead, it gives information about what can be expected in the long term. To demonstrate this, Karl Pearson once tossed a fair coin 24,000 times! He recorded the results of each toss, obtaining heads 12,012 times—only twelve off from what you would expect. In his experiment, Pearson illustrated the Law of Large Numbers.

Again, the Law of Large Numbers states that, as the number of trials in a probability experiment increases, the difference between the theoretical probability of an event and the relative frequency approaches zero (the theoretical probability and the relative frequency get closer and closer together). When evaluating the long-term results of statistical experiments, we often want to know the “average” outcome. This “long-term average” is known as the mean or expected value of the experiment. In other words, after conducting many trials of an experiment, you would expect this average value.

34.5 Probability and Sampling

In most ways, sampling from a population is not like flipping a coin, but there are some core concepts that overlap in a way that’s helpful in data science:

First, like flipping a coin, an observation of a variable in a sample has the potential to take on a range of different values. For a coin, this is pretty straightforward: heads or tails. For an observation, it depends on what you’re measuring. The possible range for the beats per minute when measuring the tempo of a Spotify song is going to be different than possible range for the beats per minute when measuring the a patient’s resting heartrate in a doctor’s office. In all cases, though, there’s a range of possible values that a given observation might take on for that variable.

Second, like flipping a coin, we expect that different observations are going to take on different values for that variable. Unless you have a trick coin, you aren’t going to get heads every single time. Likewise, not every patient at a doctor’s office is going to have the same resting heartrate. In my family, we tend to have abnormally low resting heartrates, and even though my Apple Watch gets really concerned about this, my physician isn’t worried.

Third, the Law of Large Numbers applies equally well to both. The more that we flip a coin, the closer the relative frequency of getting a heads gets to .5—the theoretical probability of that event. Likewise, the more times we measure patients’ resting heartrate, the closer the average resting heartrate in our sample is going to be to the average resting heartrate across all of humanity.

In that last comparison, you might feel like the comparison doesn’t line up as well as the two previous comparisons. It’s easy to puzzle out the “theoretical probability” for flipping a coin and to compare it to a relative frequency, but what’s the “theoretical probability” for a resting heartrate? Or any other variable, for that matter? We’ll tackle that in the next section!

34.6 Probability and the Normal Distribution

With examples like coins and dice, it’s quite easy to puzzle out the theoretical probability for given outcomes and events and work the math out from there. However, other variables are a lot trickier—there’s nothing in our DNA that indicates the probability of a patient’s resting heartrate being a particular number, and there’s nothing in the physics of sound that tells us what the probability of a song on Spotify having a particular tempo is. So, we need some way of figuring out what that probability is on our own.

Let’s look back at our example of rolling 2 six-sided dice. Even if we weren’t mathematically sophisticated enough to figure out the probability of a particular result based on “how dice work,” there’s another way that we could estimate the probability of rolling any given number: rolling 2 dice a heck of a bunch of times and recording our results. Remember the Law of Large Numbers? That tells us that the more we observe (sample) something, the more our pattern of observations resembles the theoretical probabilities associated with a phenomenon. So, if we rolled 2 dice hundreds of times, we’d start to realize that rolls cluster around 7 and get less likely as we get closer to either end of the possible range of rolls. That would be enough data for us to start to make assumptions about the probability of any given result, and those assumptions would be pretty darn close to what the raw mathematics would have told us in the first place.

What’s stopping us from doing the same thing with resting heartrates? Or tempos of songs on Spotify? Well, nothing really! In fact, that’s what researchers do all the time to establish the range of possible outcomes and the probability of getting a possible outcome within that range. (Truth be told, there’s a bit more statistical theory at the heart of this that I’m skipping over, but we’re skipping straight to the practical stuff with a warning that if you go further with data science, it’s important to better understand the theory that we’re skipping over.)

In fact, there’s a pretty good chance that if you observed (that is, sampled) a particular variable enough times, you’d end up with a pattern that’s pretty similar to what we see for dice rolls. There would be a peak right around the mean, with a gradual descent on either side. This is often called a bell curve, but we’re going to refer to it differently—as a normal distribution.

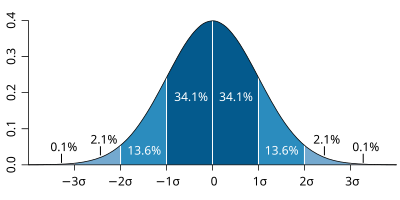

Standard deviation diagram, by M. W. Toews, is licensed under CC BY 2.5

A normal distribution looks like the image above. It peaks at the mean—that is, the mean value of the variable is the outcome that we’d expect to see most often. Then, like our dice, the probability of outcomes gets lower and lower as we get further and further away from the mean. Keep in mind that the actual value of the mean doesn’t matter—we would expect the mean of different variables to be different! A normal distribution is less about the exact numbers and more about the patterns associated with those numbers.

In fact, that’s also nicely demonstrated with some of the other things that appear in that image. In a normal distribution, there is a specific pattern for how probabilities decrease as outcomes get further away from the mean. The symbol above is the a lower-case Greek letter sigma, and in statistics it refers to the standard deviation—a concept that we covered a few weeks ago and that is worth reviewing if it’s feeling fuzzy!

In short, 68.2% of the observations of a variable following the patterns of a normal distribution will fall within one standard deviation of the mean. That is if you subtract the standard deviation for a variable from the mean for that variable, 34.1% of your observations ought to be higher than that number but lower than the mean. Then, if you add the standard deviation for a variable to the mean for that variable, an additional 34.1% of your observations ought to be lower than that number but higher than the mean. In turn, all of this means that there is a 68.2% probability that an observation will fall between the numbers that you’ve just calculated.

If you go out 2 standard deviations from the mean, your chances get even higher that an observation falls within that range. You can see from the image that it’s an additional 13.6% in each direction. Multiply that by two and add it to the 68.2% from above, and you’ll get about 95%. There’s a 95% probability that an observation falls within that range.

The normal distribution is important to understand because so much of statistics relies on these concepts. In fact, it’s customary for data scientists—and researchers of all kinds—to assume that a variable is normally distributed when we’re working with it. However, it’s also important to understand that as common as a normal distribution is for all kinds of variables, it’s not always how variables work. Just like we glossed over some theory earlier, we’re largely going to gloss over the importance of testing variables for normal distributions and alternate approaches to statistical analyses when the assumption of a normal distribution doesn’t hold up. That doesn’t mean these things aren’t important—they’re incredibly important! It’s just another thing that we don’t have time to cover because data science involves so dang much. Once again, if you continue down a data science path, it’s very important to dig deeper into what I’m glossing over here.

34.7 Conclusion

A lot of this reading is dedicated to setting the groundwork for future concepts, so if it’s not obvious how things fit together right now, that’s okay! What you ought to take away from this reading for now is: 1) that data scientists nearly always work with samples instead of populations, 2) that larger, representative samples better approximate populations than smaller, non-representative samples, and 3) with a larger sample (one with more observations), we can get a pretty good feel for what the probability of a given result is.

Furthermore, like some other recent readings, our walkthrough for this week is going to cover sampling again, though not necessarily all of the details that we’ve covered here. This is less about being redundant as it is about covering an important concept multiple times from multiple angles.